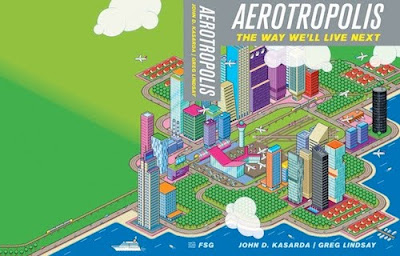

Aerotropolis: The City of the future

International airports have developed overtime into key nodes in production and enterprise through agility, speed and connectivity. These transportation hubs are able to dramatically stimulate local economies by attracting aviation related businesses and their peripheries and resulting in what John Kasarda, a US academic who studies and advises governments on city planning issues, has dubbed the “Aerotropolis.”

The Aerotropolis like any other traditional city, consists of a central core with rings of development permeating outwards; unlike a traditional city, however, the city’s core is an airport and all neighboring development supports and is supported in turn by the airport industry.

These words certainly have not fallen on deaf ears. Airport cities have already appeared in Amsterdam Zuidas, Las Colinas, Texas and New Songdo, South Korea‘s international business District. Dubai is currently considered to be the world’s largest aerotropolis, connecting the East and West primarily through international air travel and commerce; however, OMA has just revealed masterplans for a competitive airport city in Qatar.

These words certainly have not fallen on deaf ears. Airport cities have already appeared in Amsterdam Zuidas, Las Colinas, Texas and New Songdo, South Korea‘s international business District. Dubai is currently considered to be the world’s largest aerotropolis, connecting the East and West primarily through international air travel and commerce; however, OMA has just revealed masterplans for a competitive airport city in Qatar.

Business Insider: http://www.businessinsider.com/aerotropolis-city-of-the-future-2013-3

The Aerotropolis like any other traditional city, consists of a central core with rings of development permeating outwards; unlike a traditional city, however, the city’s core is an airport and all neighboring development supports and is supported in turn by the airport industry.

Several airports around the globe have organically evolved into these airport-dependent communities, generating huge economic profits and creating thousands of jobs, but what Kasarda is arguing for is a more organized and purposeful approach to the development of these Aerotropolises – what he believes to be the future model of a successful city.

Looking back on city development, it quickly becomes clear that cities have almost always been an outcome of and had a strong relationship with the form of transportation that was relevant during the time of their establishments. In the US, the first modern cities developed around seaports (Boston, Charleston, NYC) and then towns popped up along rivers and canals (Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Detroit).

Next the invention of the railroad opened up previously hard-to-reach inland areas to manufacturing and distribution (Atlanta, Omaha, Kansas City). In the 20th century, highways facilitated the greater dispersion of people and companies by creating suburbs, and most recently, the world’s airports have turned into “primary drivers of urban growth, international connectivity and economic success.”

Kasarda claims that the cities that will thrive in the 21st century will be those with airports and their centers, for “efficient, large, well-connected airports matter to prosperity above everything else” and “the fastest, best-connected places will win.”

Plans for a China Southern Airport City by Woods Bagot are underway, as well – in fact, China is reportedly building a total of 100 airports to be completed by the year 2020. Nearby Taiwan has allocated $8 billion for just one airport while the US allocated a similar amount – $9 billion – for all transportation infrastructure in 2008. With this kind of indifference towards its airports, Kasarda warns that America’s economy runs the risk of falling behind these other developing nations.

A nation’s airports are undeniably vital contributors to the economy. Chicago‘s O’Hare International Airport is the 2nd largest office market in the Midwest and Washington Dulles’s airport area alone has more retail sales than any other American city besides Manhattan. Detroit, a city that is seriously considering a new airport development to stimulate its struggling economy, would generate $10 billion in annual economic activity, $171 million in annual tax revenue and would create and sustain 64,000 jobs after 25 years. Why would anyone living in Detroit today frown upon a proposition like this?

Well, while the economic effects of the Aerotropolis are clear, its effects on an existing urban fabric and its people are much less so. This is evident in the current issues facing London and its new major airport in southeast England, a task that has drawn many of the world’s leaders in business, planning and architecture.

After considering the Aerotropolis city model, Rowan Moore of The Guardian finds it “chilling: a model of a city driven by a combination of business imperatives and state control, with the high levels of security and control that go with airports. Under the dictatorship of speed, individual memory and identity are abolished. An airport shopping mall is, actually, not like a town square [as Kasarda suggests], for the reason that everything there is programmed and managed, and spontaneity and initiative are abolished.”

In addition, he notes that Kasarda’s model envisions the Aerotropolis being constructed on “virgin greensward,” which is simply impossible for London and most existing metropolitan areas. It turns into a challenge of reorienting an entire city to focus on its airport – a monumental effort when working with a metropolis that has hundreds if not thousands of years of history and urban growth. The model could work seamlessly where there’s a blank slate, but there just aren’t enough of those left in the world.

While the Aerotropolis vision is an economically enticing one and has already set many gears in motion around the globe, we need to stop and consider the bigger picture: how will this model change the way we experience cities? Will individual culture and character be lost to the fast-paced, constantly-connected and homogenized aura of air travel or allow for a greater cultural exchange? How will it affect the human psyche and will the preoccupation with money and control eventually replace all other knowledge or will it create new knowledge as a result?

What do you think?

Business Insider: http://www.businessinsider.com/aerotropolis-city-of-the-future-2013-3

Comments

Post a Comment